3 Conclusions

THOROUGH APPRECIATION of Alwyn's work requires work on the part of the beholder. This does not imply that it is difficult to listen to his music purely for pleasure: on the contrary, his gifts as a melodist and creator of aurally effective harmonies were themselves enough to ensure from audiences a warmer reception than was granted to many of his contemporaries, especially in the 1950's to 1970's. Plenty of reviews (reproduced in a catalogue of Alwyn's music published by Lengnick in 1958) in newspapers testify to the way in which his "vitality and lyricism", "courage of convictions ... a straightforward beautiful tune", "friendly harmonic idiom and vivid imaginative scoring" brought "solace to honest music lovers who try to come to grips with contemporary music" and bridged the "gulf that often exists between the contemporary symphonic composer and the general public".

Reviews in specialist magazines such as the Musical Times were not always so kind, which is acceptable when the opinions expressed are genuinely held and accurately researched by their authors. This was not always the case, as is shown by Hugh Ottaway's description (following a performance conducted by Beecham) of much of the Third Symphony as "gestures of a talented rhetorician without a real sense of momentum or cogent follow through" (Musical Times, December 1956, p 645). The account of the work in the previous chapter demonstrates that the phrase about lack of cogent follow through is wrong, and if there was a lack of momentum, that could be the fault of the performer rather than the composer: however, the phrase "gestures of a talented rhetorician" is an opinion to be respected whether or not one agrees with it.

The problem with the publication of derogatory statements in respected journals is that readers are thereby discouraged from performing or listening to the music being described: those with no general interest in the genre or other aspect of the works involved will not have their curiosity aroused; and those who are inclined to interest, but are not immediately able to consult the music itself, may overlook the chance to form their own opinions.

One hopes that we now live in sufficiently enlightened times that remarks like "no place in a festival of contemporary music" (Martin Cooper about Autumn Legend (Musical Times, September 1955, p 489) would be answered by the forthright hoots of derisive laughter they have always deserved, on the grounds that they display failure to understand the term "contemporary". Contemporary music is the music being composed at the time, regardless of idiom: what matters is whether it is composed well enough to be sufficiently effective in performance to give pleasure. Mr Cooper went on to denounce Autumn Legend as repeating "what has been said more effectively and with force of creative originality by other (men)". If one interprets this as meaning that in his opinion this work is not effective enough to merit further performances, one should respect his view whilst feeling free to form one's own: to imply that better works exist, and for that reason this one has no place in the world, is a false value whose logical outcome is that only one work (the best) in each genre should ever be performed.

This failure of Alwyn's music to find critical favour in the right circles was by no means universal, but must have contributed to its neglect. In accordance with the composer's ideals, his music speaks directly to those who listen to it for the sheer pleasure of hearing its sounds, and is liable to go over the heads of those for whom intellectual satisfaction is a high priority. This is unfortunate for, as analysis of the Third Symphony shows, there is plenty to fascinate the technical analyst who is prepared to investigate such a work. This was of vital importance to Alwyn - this is why in 1939 he took the radical step of disowning all his work on the grounds of shortage of technical competence (he later called it lack of professionalism), and immersing himself in the study of the scores of composers he admired.

Alwyn was as earnest a believer as anyone in the value of experimentation as a contribution to maintaining the freshness of artistic invention. In The Technique of Film Music, he wrote "a composer should always experiment ... if a composer is absorbed in his work it will stimulate something ... which has ... symptoms of novelty". Unlike many avant-garde artists and their supporters, he was shrewd enough to realise that experimental approaches to the technique of art should be means of stimulating the imagination, not ends in themselves. Many words in Daphne are devoted to explaining this ideal: Alwyn noted how many followers of the avant-garde made judgments using the wrong criteria, acclaiming the latest works of art for the sake of the methods and techniques used to produce them, with scant regard for the sensations (if any) aroused by them, and mistaking mere newness for originality. He lamented the way in which some genii (he cited Stravinsky and Picasso as examples) who had created great works of art eventually wasted their talents in feverish experimentation for its own sake. Daphne and Apollo, the sculpture by Bernini on which Alwyn hangs his aesthetic credo, is shown to define beauty by providing a pleasurable sensory experience as well as illustrating apparent perfection in the technique of its creator.

One hopes that those dark ages, when the opinions of those who applied the aforementioned false values were more influential than those based on genuinely artistic criteria, are over, and there is now a climate in which music like Alwyn's (wherein technical matters are a stimulus to true creativity) may flourish. In 1982 Jill Gomez bemoaned opera houses' lack of interest in Miss Julie, attributing that to the work's failure "to go plink-plonk-plink" [Quoted by Herbert Culot in "William Alwyn", British Music Society Journal (1985), p 23], but Alwyn himself was sufficiently perceptive and far-sighted to realise (in an interview given to the BBC World Service in 1981) that the dawn of a more enlightened era had arrived.

Given the composer's concern that one of the routes by which art must appeal is through immediate sensory experience, it is ironic that there are a number of areas in which further exploration is required in order to appreciate Alwyn's work. His aesthetic credo is set out in detail in a literary work whose title is Daphne, or The Pursuit of Beauty, and there are many occasions, in his writings and recorded thoughts, on which he implied that his creative life was an unremitting search for beauty. In a letter to Trevor Harvey, enclosing a copy of Daphne, he wrote "the search for beauty is what means everything to me". The terminology heightens the danger of his ideals being perceived as sentimental, whereas investigation into what he meant by "beauty" shows that he had in mind something more wide-ranging, approximating to artistic excellence in general. The obvious way to find out what Alwyn meant by "beauty" is to listen to his music, look at his paintings and read his poems, especially Daphne, in which he writes "Beauty is seen, heard, felt ... eludes attempts at definition. Beauty is truth, and truth is beauty", and in the succeeding sixty pages explains and develops his ideas and ideals about what does and what does not constitute art in general, and great art in particular, illustrating specific points by very perceptive references to works and their creators and critics, and frequently referring to Bernini's sculpture as the work of art that comes closest to epitomising his hypothesis. "Daphne is beauty, not the solution to a logical problem".

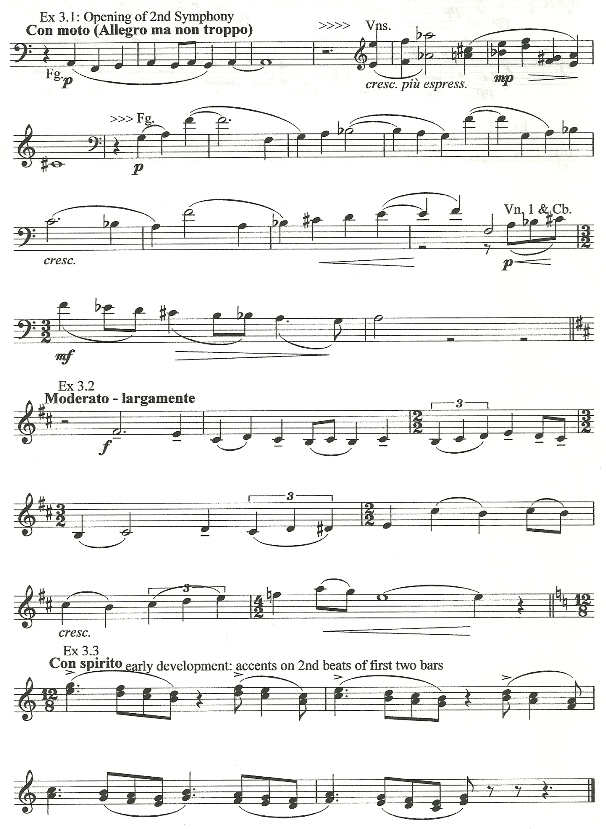

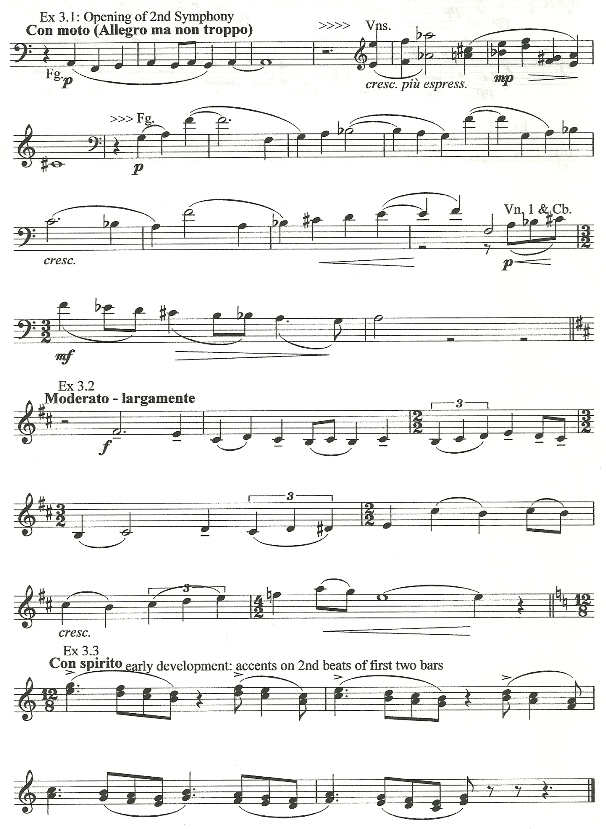

There are others, besides those who believe that technical innovation should be the primary motivation for new music, to whom Alwyn's work will not appeal. It will not find favour with those who dislike overt romanticism expressed in grandiose gestures such as big tunes and loud, emphatic climaxes. There was no room in his philosophy for being ashamed of any means of expression provided it represented what he genuinely wished to communicate, and satisfied his technical requirements by arising logically in the course of composition so it did not appear inapt. In addition to those already noted in the Third Symphony, a fine example may be found in the Second Symphony, which is concerned with the transformation and development of three related themes heard at its beginning (Ex. 3.1). Late in the work this process gives rise to a big, lyrical melody in D major (Ex. 3.2).

Neither does Alwyn's music appeal to those who appreciate forms in which themes may be clearly identified as principal motifs or subjects, or become easily recognisable by reason of repetition at expected junctures, as in sonata or rondo form. His view was that romanticism is inhibited by such forms: he cited Brahms and Elgar as examples of composers whose symphonies are struggling to escape formal boundaries (Interview for BBC World Service, 1981). He complained about "misguided attempts to pigeonhole my music into forms", because he preferred to compose by allowing his ideas to grow and develop from each other as the music progressed. It is not surprising that he admired Liszt and Wagner, since his method is an extension of their ideas about transformation of themes. Undoubtedly asking the question "What form is it in?" would impede the appreciation of a work by Alwyn.

One result of this method inhibits popularity, namely that, despite his gifts as a melodist, Alwyn's tunes tend not to be memorable, if only because they are not repeated frequently enough. The nearest to an exception is the Festival March of 1951, a thoroughly effective ceremonial march in the manner of Elgar and Walton, whose main theme (Ex. 3.3) has a swinging swagger (reminiscent of Alwyn's fellow townsman Arnold) heightened by the judicious placing of rests on important beats and accents off them. As in all his works, Alwyn cannot resist transforming and developing his material.

Very few people are likely to be alienated by Alwyn's harmonic language, and most who are will also object to the romanticism. Those that remain are those whose taste is for straightforward harmony whose dissonance does not venture beyond that which is classically prepared and resolved. Alwyn's use of dissonance became more and more assertive as his career progressed, linked to his experiments in finding new ways of organising tonality. The Violin Concerto (1937-9) contains little that is more adventurous than chords of the sixth and seventh; at the other end of his life the Concerto for Flute and Eight Wind Instruments (1980) contains textures and pungent harmonies reminiscent of Stravinsky's writing for similar forces. In the scherzo of Symphony No 4 (1959), one of the works in which the chromatic scale is divided into modes of eight and four notes, there are exultant, outrageous clashes between scales and change-ringing motifs in sharp keys (one mode consists of the major scales of D and A) and flat keys invoked by the other mode (B flat-C-E flat-F). This passage (a rare example in Alwyn's work of overt musical humour) is easy on attuned ears, but probably sounds horrendous to others.

Lastly, there may be those who cannot accept that musical ideas, like philosophical ideas, are not always completely and accurately definable - this is applicable especially when the themes are in a state of continual progress, growth and development. Just as he felt the need for 65 pages to satisfactorily explain his ideal of beauty and why that ideal is not definable, at the end of an Alwyn symphony it may well be unclear which (if any) version of a given motif is definitive.

Several of the reactions discussed in the preceding paragraphs are matters of personal taste, in that they are determined by the senses and cannot be altered by conscious effort: there is no reason to suspect that this type of antipathy to Alwyn's music is more widespread than is the case with any other composer. The other objections may be overcome by the adoption of enlightened attitudes and the use of a complete set of appropriate criteria when making judgements about the quality of works of art.

One complaint that used to be made about Alwyn's orchestral concert music was that it sounds like film music. This opinion does not appear to have been voiced recently, so hopefully it has been overcome. It is as absurd as stating that his film music sounds like concert music, because he applied his style and methods to each branch of his art in such a way that the two inevitably sound like each other: the correct assessment to make is whether his skill as a composer was sufficient for both to be convincing. Alwyn was undoubtedly keen that his concert works should be judged in their own field and not in conjunction with his film music: the disparaging comments are almost certainly the reason for his refusal to arrange suites of his film music for the concert hall. He was aware of things in his film music, necessitated for example by the portrayal of specific human emotions, which would be inappropriate in his other orchestral music. He would never have considered including in a concert work lush romanticism as over-the-top and cliché-ridden as the love theme Christabel or the Utopian Sunset from The History of Mr Polly (1949), or a representation of fear such as Paris and Flight from The Fallen Idol (1948).

Nothing that can be found by studying Alwyn's music or the philosophy behind it explains the neglect which it has suffered. Neither is there any evidence that it is exceptionally difficult to perform - he was concerned to avoid such an eventuality, having learned a lot from his experience as an orchestral flautist about making sure his music was practical, and suited the instruments for which it was written. His own expression for this (Interview for BBC World Service, 1981) was that when writing he was "sitting beside each player" to ensure he would not struggle and could give an excellent performance.

Analysis of Alwyn's aesthetic and philosophical works (notably Daphne and Winter in Copenhagen) reveals him to have been the possessor of a highly intelligent, perceptive, enlightened and scrupulous mind, passionately concerned about the future of art and the integrity of artists and their works - indeed, about integrity in general. Analysis of his music, combined with listening to it, reveals the successful application of these ideals to his own compositions and shows that, given that there are a large number of people who appreciate romantic music, there is no reason why Alwyn's works should have any difficulty making a case for their continued performance. The means by which they may make that case is simply by being performed well and heard.