2 The Third Symphony

ALWYN'S THIRD SYMPHONY made a strong impression when new, in 1956. Reactions to early performances ranged from "The finest British symphony since Elgar's 2nd" (John Ireland) to "Music without a face...the best bad symphony of the month" (Hugh Ottaway: on another occasion, this same reviewer referred to the "directness of communication, warmth of eloquence and freedom from esoteric pretentiousness" of Alwyn's Lyra Angelica (Musical Times, December 1956 and September 1954 respectively). This chapter concentrates on the composer's impressive craftsmanship, the technical means by which he assembled such a striking work.

The symphony is set in E flat major, although the key centre at the beginning of both first movement and finale is C. Instead of using conventional diatonic harmony, Alwyn divides the chromatic scale into two modes, to one of which (eight notes: C, D flat, E flat, F#, G, A, B flat, B) he adheres strictly for the entire ten minutes of the first movement and most of the finale. The other four notes (D, E, F, A flat) provide the material for the first four minutes of the slow central movement, and then become integrated into the whole by a process explained below.

First movement

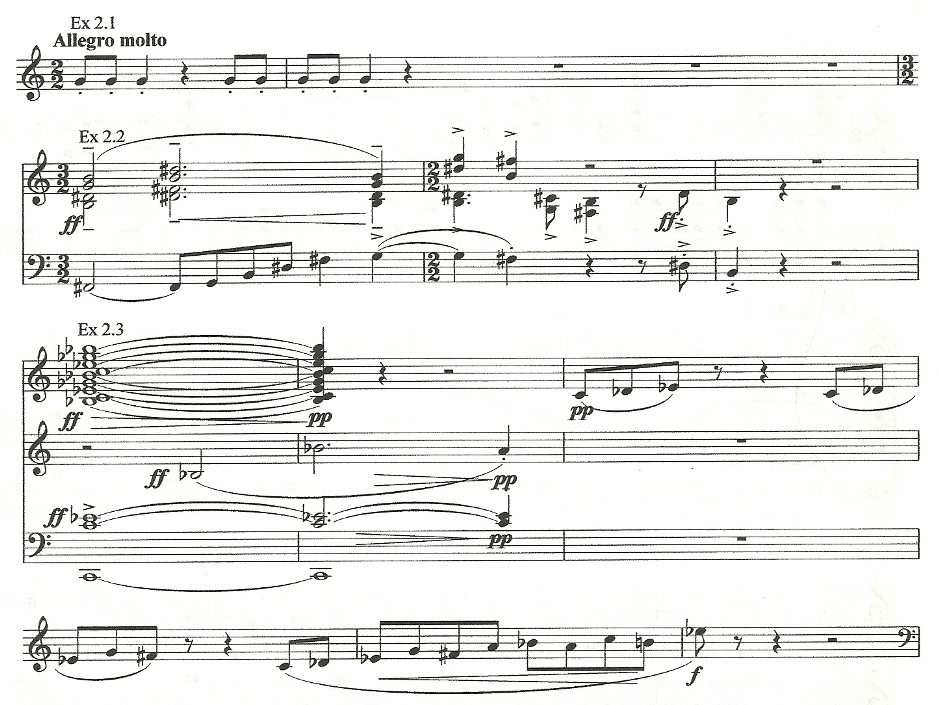

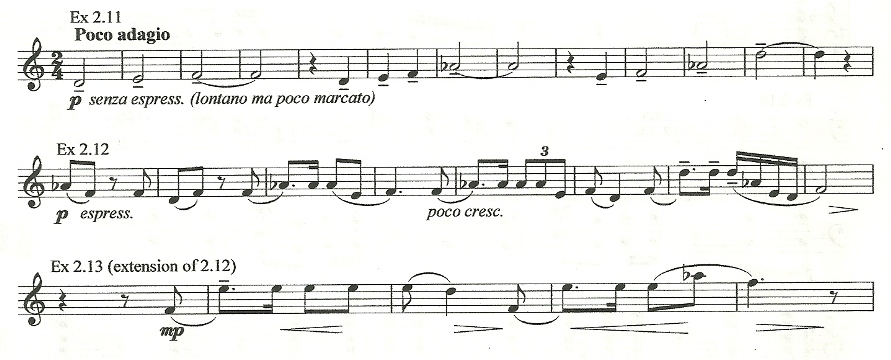

The work opens with the first protagonist, the rhythm Ex 2.1.

The first product of the mode to be explored is the augmented triad B-D#-G and the possibility of its resolution into B major (Ex 2.2): this opening gambit creates harmonic tension because B major is the most distant from E flat of the available resolutions. Instead of confirming this resolution, a trill on F# explodes into a chord consisting of C, E flat, G flat and B flat, C becoming the first pedal (it is characteristic of Alwyn to anchor the harmony by using bass pedals) and tonal centre. It is interesting to ponder how one should describe this chord in this context: one may argue that, because A flat does not exist in the mode with which the composer has chosen to work, one cannot call it a ninth chord with A flat as root; or that one may use this description because Alwyn is using diatonic harmony but choosing not to sound certain notes.

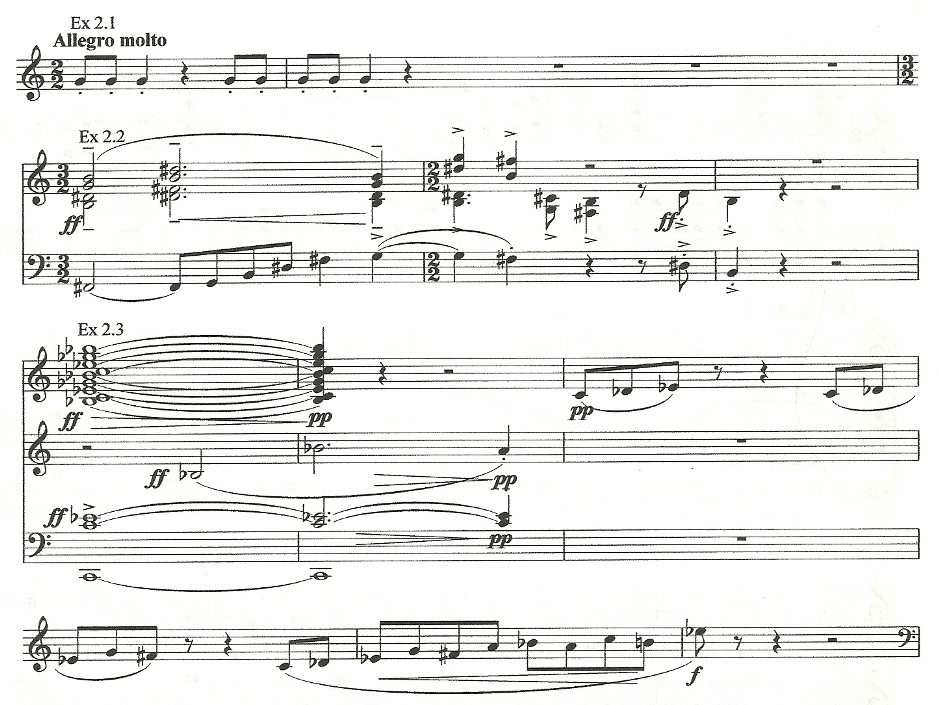

By the time we reach letter C [Throughout this chapter, bold type is used to denote rehearsal letters as defined by the miniature score (London, Alfred Lengnick & Co, Ltd., 1957), e.g. H+4 means four bars after H] in the miniature score, we have already passed several examples of how this work is tautly bound together by close relationships between themes that grow from each other. The bass line of Ex 2.2 is the seed of ideas (e.g. the first two bars of Ex 2.3) related to the motto theme (Ex 1.1) running through Alwyn's first four symphonies and featuring leaping octaves and sevenths; two themes - the exposition of the mode beginning at bar 3 of Ex 2.3 (this is also a legato version of the work's opening rhythm), and the first theme to feature triplets (of rhythmic importance later), Ex 2.4 - have already lead to the note E flat, the major key of which is the ultimate harmonic goal of the symphony. Ex 2.4 is the second statement of this theme, quoted in preference to the first because it begins with the notes G-F#-E flat (in itself a crucially important motif); and the previous bar (first bar of the example) contains a chord (F# minor triad + E flat) that is destined to play a role as important as the dominant seventh in conventional harmony, and a bass line related by inversion to the bar before A, from which springs the fifth bar of the theme.

At C the bass, having passed through E flat en route from C, reaches the note A. A descending motif, given to two trombones and harp, consisting of the notes of the mode from C down to E flat threatens to supplant this new pedal as bass line. The motivic threads of this passage (Ex 2.5) emphasise seconds (minor and augmented) and the diminished chord (E flat - F# - A - C) that is contained within the mode. Tension is created by the addition of D flat to this chord, and especially by the bass pedal rising to B flat while these motifs and a 'cello ostinato A-F#-G-A continue.

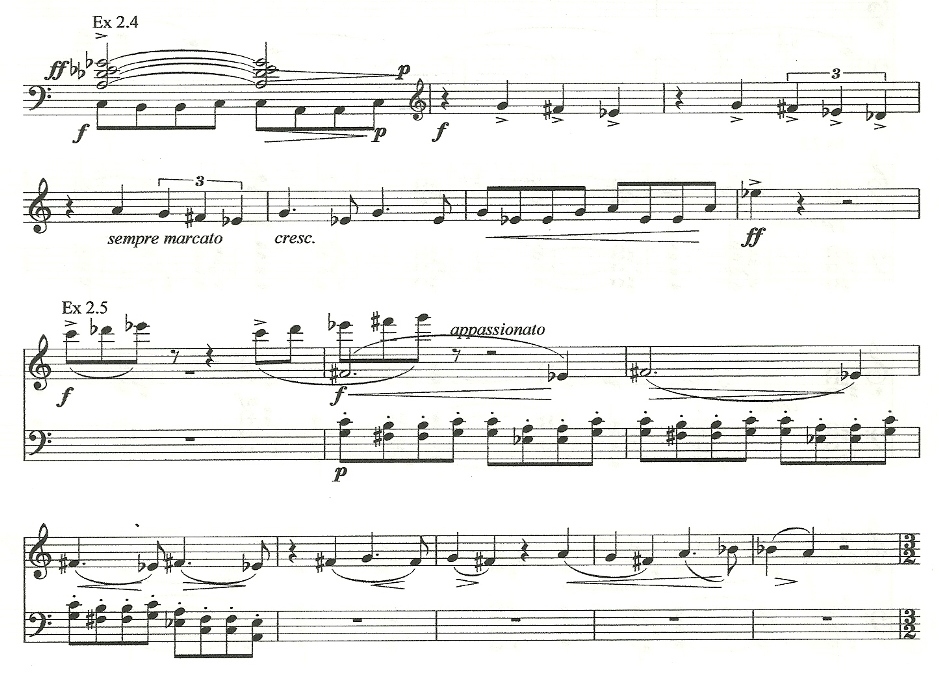

The strings begin at E an expressive counterpoint involving a descending fourth (E flat - B flat), briefly suggesting a new direction, but the music soon returns to the matter in hand, emphasising the diminished chord while the B flat (dominant) pedal continues until after F. Further development of melodic and rhythmic material, involving chords of E flat minor and C flat major (D flat added) resolves in a more lyrical ("Piu lirico") passage beginning fervently with a climax in B major (H+4: Ex 2.6) but with F# as bass, leaving the melody to concentrate on the note B. The note G, in the work's opening rhythm or as a timpani roll, is a lurking presence: it is characteristic of Alwyn to colour a chord with a dissonant note, which in this context has the specific function of keeping us mindful of the (Ex 2.2) augmented chord and its proposed resolution. Towards the end of the long diminuendo which thus begins, the bass slips from F# to C#, then A, which becomes the next pedal. Significantly, at this moment of stillness appear the notes of the triad of F# minor, the symphony's secondary key centre, which is the most remote possible from E flat major within the eight notes to which the composer has restricted himself.

A brief suggestion, in the bassoon parts at K+5, that Alwyn is about to explore the inversions and retrogrades of his mode-outlining idea (Ex 2.3) disappears into a long passage in which the opening rhythm (Ex 2.1) is the driving force. An aggressive outburst establishes G (bass) and B as harmony notes, then Ex 2.1 becomes a disquieting undercurrent to a theme in long notes. The statements of this melody (Ex 2.7) are not identical: they are related to each other by overall shape and rhythm in such a way that the theme is constantly evolving, along with its instrumentation and harmony (which reaches F# minor at the climax), and becoming more fervent throughout the continuation of the 'cello version and subsequent re-entry of the violins. The augmented chord that has governed much of the work so far is described twice in this passage: by the combination of first melody note and harmony notes, and the first notes of the three statements of Ex 2.7.

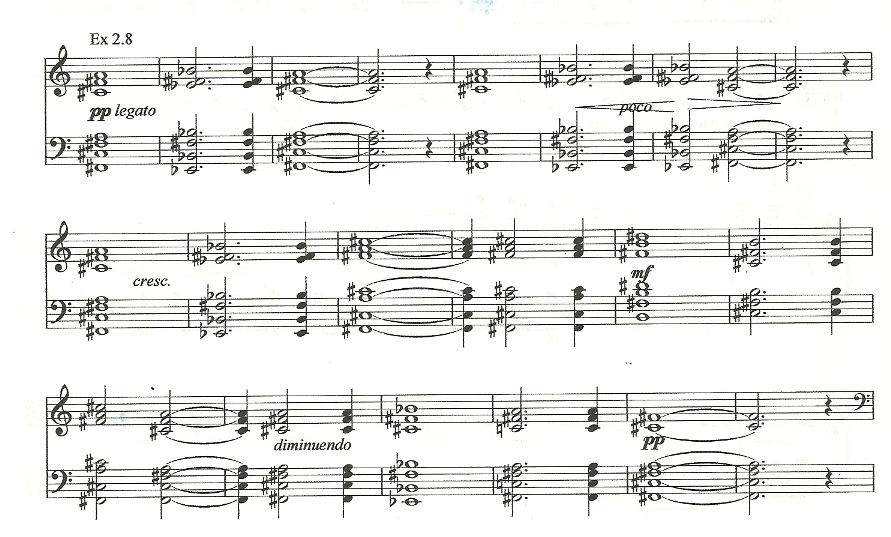

More ostinati underpin developments and juxtapositions of familiar chords and melodic strands ("octave leap" idea from Ex 2.3, and Ex 2.4) until brass introduce a broad, chordal theme (summarised in Ex 2.8) in F# minor, made by first alternating that chord with E flat minor then expanding the idea, including B major. The whole is enlivened and the fast tempo maintained by syncopation in the melody and agitation in the accompaniment. In common with Ex 2.7, Ex 2.8 is immediately repeated twice: this time the variations are not in the melodic shape, but in the orchestration (wind, then louder and more broadly in triplets in the strings) and in counterpoints and interjections from a solo trumpet, then wind and horns. An ostinato extension of the motto octave leap runs through the brass and wind statements of Ex 2.8, binding this passage securely into the whole work. As a subtle link with one of the movement's harmonic driving forces, in the string version of this theme the F# of the B major chord is replaced by G.

Following some agitated music examining the available tritones, the diminished chord and the G-F#-E flat motif, at Z-2 the bass moves up from A to the dominant B flat ready for a quiet, chordal exploration of another possibility (the longest available chromatic ascent, from A to C#) acting as accompaniment to an idea (Ex 2.9), discovered in the viola and 'cello parts, which is destined to dominate the rest of the movement. In these remaining bars Alwyn draws together the threads of the symphony so far - a process at least as satisfying as the classical recapitulations that he found long winded and inhibiting. G-F#-E flat appears immediately (in Ex 2.9): when it is harmonised at CC-10, we find in the bass the equivalent of the progression IV-V-I: because A flat is unavailable A natural takes its place as IV, and because its chord is unavailable V is presented as the root of chord Ib. At AA woodwind and brass begin the apotheosis of Ex 2.7, the natural continuation of which turns out to be the "drawing together" theme from Ex 2.9: meanwhile low brass and strings forcefully interject the "mode exposition" Ex 2.3, now beginning on the keynote so that the first group of three notes becomes E flat-F#-G. Further interjections begin on C (the first key centre) or F# (the secondary keynote).

A quiet, calm reiteration, without interjections, of the aforementioned apotheosis ends in alternation of the notes G and F#, stirring again the argument about the augmented triad that began the work at Ex 2.2, and generating a crescendo and accelerando to FF. The composer now shows us that B major was the wrong resolution of the augmented chord, the correct route being via its combination with F# minor to chord Ib of E flat major (Ex 2.10). The incorrect resolution has generated ten minutes of harmonic symphonic argument, which is now resolved in a reminder of the rhythmic passage in which the incorrect resolution had its exposition.

Second movement

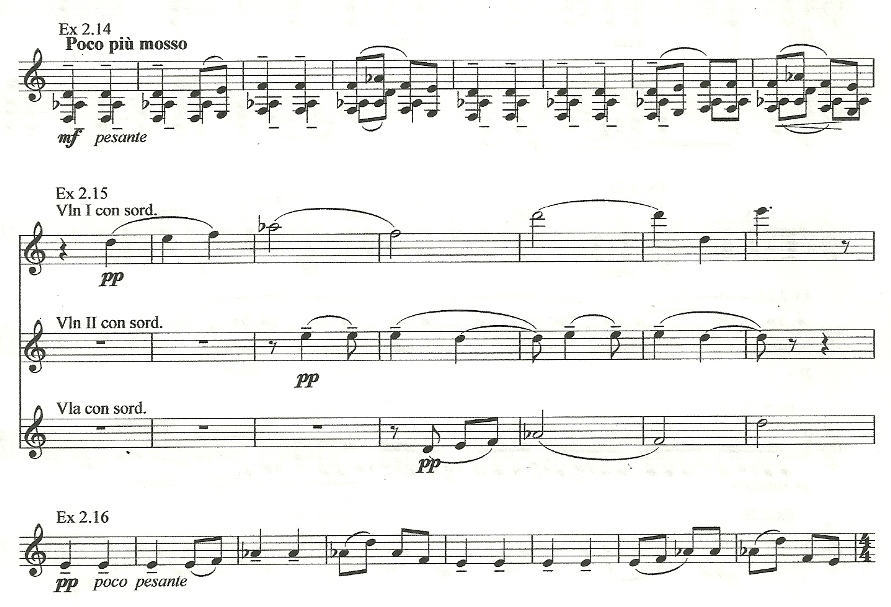

Alwyn exploits the lack of warmth and shortage of consonant intervals in his chosen mode. Indeed, he exacerbates these aspects by not using enharmonic equivalents: whereas in the first movement he did not hesitate to use (for example) both F# and G flat, now he adheres strictly to A flat when the use of G# would have made a major third available. Thus the only intervals are major and minor seconds, minor thirds, their inversions, a tritone, and a diminished fourth (E-A flat, which must resolve to the minor third F-A flat) and its inversion. These bring to the music qualities of remoteness and exoticism, felt especially when the two minor thirds D-F and F-A flat clash with E: the third melodic idea (Ex 2.14), in quicker tempo, sounds like a sort of middle eastern march. Militaristic fanfare-figures intrude, first slowly in the clarinet parts in accompaniment to the 'cellos' statement of Ex 2.13, then menacingly and insistently as the march theme builds to a climax. These fanfares and the persistent rhythmic ostinati of the outer movements are connected with the composer's aversion to war, one of a number of thoughts of great importance to him that he expressed forcefully in his poem Winter in Copenhagen.

At H a quiet, canonic and imitative passage for strings (Ex 2.15), referring to the exposition of the mode (Ex 2.11) with which a solo horn began the movement, prepares the way for the introduction of the first movement's mode, initially in the form of a pedal B flat. This immediately brings warmth to the harmony by creating a major third with the D with which the basses re-enter after 28 bars' silence, dispelling the tension caused by the previous shortage of consonance and generating a serene, fanfare- and percussion-free centre to this movement and the whole work.

Until now there have been very few harmonic possibilities in this movement. After a reminder (horn: related to Ex 2.9) in the rhythm of this movement's Ex 2.13 of the "falling semitone then minor third" motif from the first movement, Alwyn makes the most of the brief availability of all twelve notes in a triadic version of Ex 2.12 (strings, pp dolente). A solo flute ascends to remind us of the original accompaniment to the march theme Ex 2.14, which promptly resumes at L in the home mode but transposed one degree upwards (Ex 2.16), making much more difference to its shape than if the composer were using a conventional scale. A very dissonant (using only the notes E and F) reminder of the fanfares and a faster, declamatory imitative passage (related to Ex 2.15) using all four notes culminate in a colossal climax, in which rapid passagework and forceful dotted rhythms in the home mode are underpinned by B flat in the bass. This section (L to P) proposes that after the more richly harmonic middle section, the four note mode is so unstable as to necessitate a massive affirmation of its relationship to the home key of the symphony, namely that the addition of B flat in the bass creates the dominant seventh, albeit with an exotic added tritonic E natural.

Once the music has quietened, the dominant seventh is indeed followed at Q by its tonic - not a chord, but an E flat in the bass as the movement's drawing together of threads begins. While the cor anglais extends Ex 2.12 into an imitative accompanimental figure shared with a clarinet, something very strange and apparently inexplicable occurs in the bass: the E flat is succeeded by B natural, then C# - none of these three notes belongs to this movement. A solo muted horn repeats the first three notes of the movement before the music dies away with first violins (who have throughout this final passage been recapitulating the canon theme Ex 2.15) and 'cellos augmenting the first two notes of Ex 2.12, in the process resolving the last E natural.

Third movement

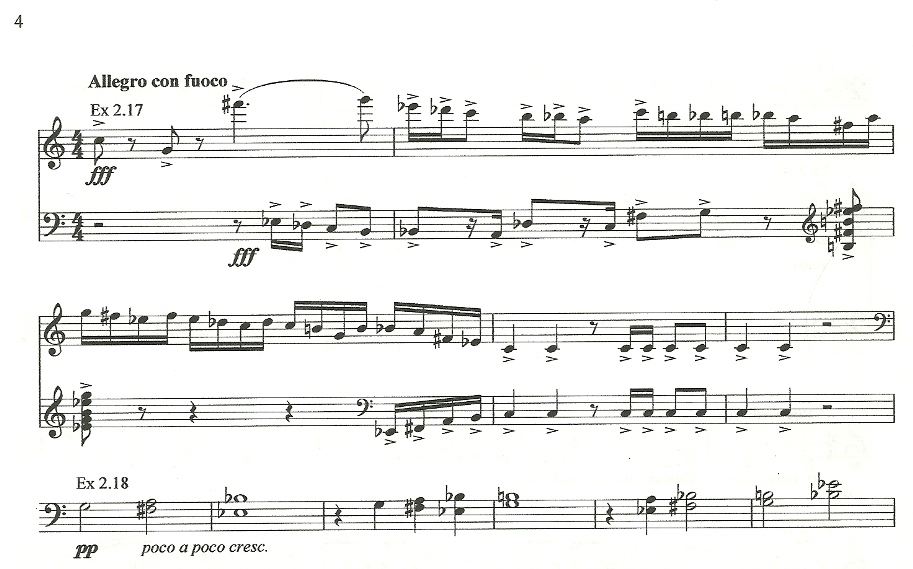

The extremely forceful opening (Ex 2.17) hurls a number of important elements into the air. The first bar and a beat contain within the theme a striking appoggiatura and a rhythmic cell (two semiquavers + quaver) consisting of the notes E flat-D flat-C (and at the beginning of the third bar G-F#-E flat), groups which are destined to be as important in this movement as they had been in the first. The first of these groups begins the counterpoint that anticipates the menacing rhythm, established by bar 5, which is destined to dominate the first few minutes of the movement. The two chords are familiar from the first movement where they appeared in reverse order, B major being the apparent resolution of the augmented chord. This time it seems that G is the resolution of F#, as in the appoggiatura. Another feature this opening has in common with that of the whole work is the key centre of C.

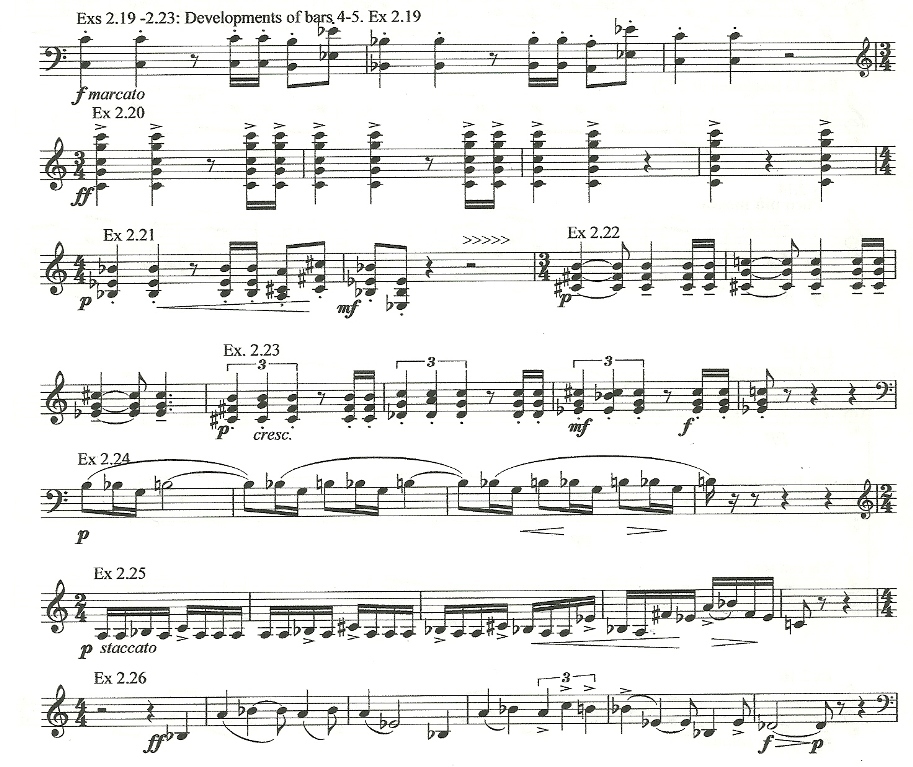

A theme in long notes makes an appropriate contrast. One (Ex 2.18) soon appears, setting E flat minor against the insistent C in the bass and utilising G-F#-E flat as its bass line. The stepwise motion of Ex 2.18's upper line soon affects the omnipresent rhythmic accompaniment (Ex 2.19). The volume soon rises to fortissimo to remain there for some time, an F# being added to the C of the rhythm in an extended version of the first bar's appoggiatura: after 14 bars the F# resolves to G. Briefly the rhythm assumes a triple time form (Ex 2.20), heralding a section developing the material of all of the first four bars.

Unusually, in this passage the harmony is not anchored by bass ostinati. Rhythmically quaver + two semiquavers (usually legato) turns out to be as important as two semiquavers + quaver (usually aggressive and marcato). The former becomes prominent in a 'cello melody (Ex 2.24) using the "falling semitone then minor third" idea familiar from the first movement: the notes (B-B flat-G, then in the viola version G-F#-E flat) are the same as in that movement's triplet motif Ex 2.4. The key centre twice progresses C-E flat-F#, and when Ex 2.24 reaches the violins it becomes A, completing the outline of the diminished chord. At K the introduction of the key of E flat minor, in which A appears to be an appoggiatura, casts doubt on the note's status, but a new rhythmic idea in duple time (Ex 2.25) reaffirms it as the key centre.

Further development emphasising the diminished and augmented chords leads to a climax representing a major change in the music, which ceases to be driven by rhythm. The bass settles on E flat, the symphony's keynote and the note common to the two chords, and against a swirling accompaniment encompassing E flat major and minor, the augmented chord, G-F#-E flat and B-B flat-G, horns and 'cellos proudly present a theme (Ex 2.26) clearly connected with at least two important motifs from the first movement, Exs 2.3 (first two bars: by inference the motto of the four symphonies) and 2.7 (implying also Ex 2.9).

The combination of so many important themes may mislead one into thinking this movement's drawing together of threads has begun, but there is another protagonist to be considered.

This is the four note mode, which makes a startling entry at Q-2 in a dissonant shock wave that is soon dispelled, leaving timpani tapping out Ex 2.20 in support of woodwind gropings. The introduction of fanfares (as in the slow movement) marks a crescendo into a passage setting out to integrate the mode into the work as a whole, using the imitative, contrary motion version of Ex 2.18 and beginning with the notes B and C#, explaining their appearance in the bass near the end of the previous movement (now that has been shown to be anticipation of the passage from S-6 to T in the finale, the strangest thing in the symphony is the use at S-7 of G and G flat in the violin parts and a D# ending a trill: there is no apparent reason for deviation from the four note mode + B + C#, to which this passage is otherwise confined. The appearance at S of C as auxiliary to a first violin trill is also odd, so much so that one wonders if the part should be in unison with the other strings, and that C is a misprint for A flat).

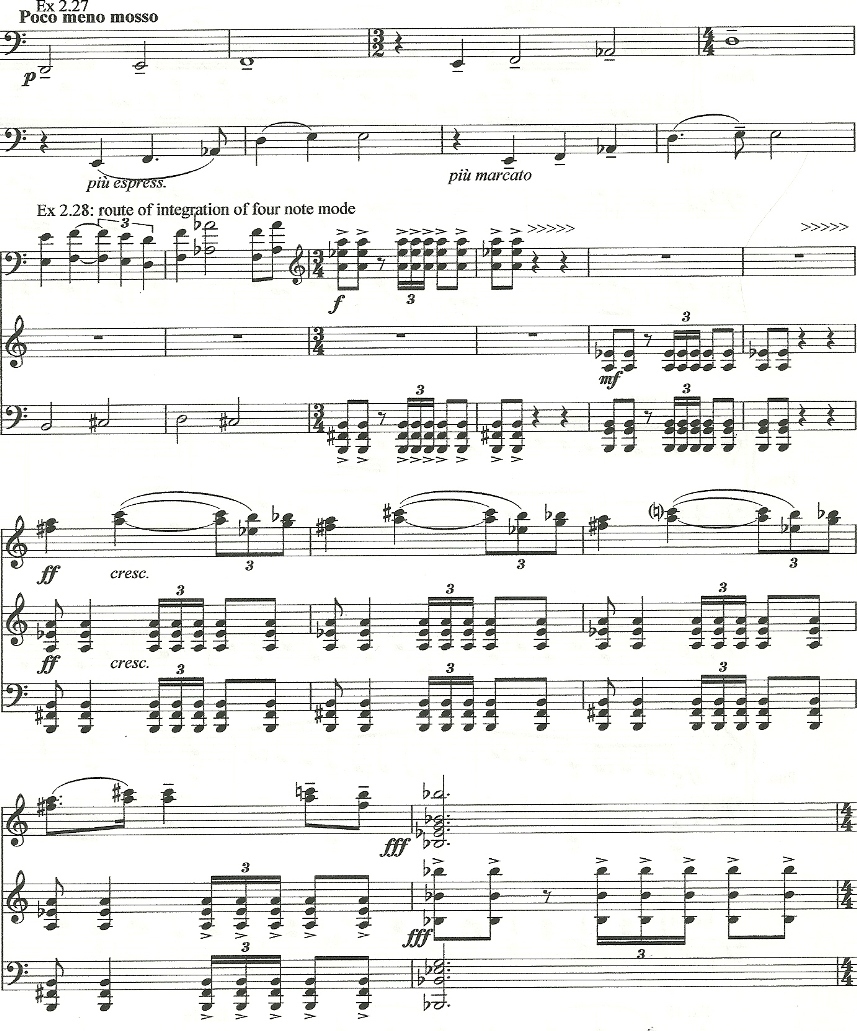

Meanwhile, a solo tuba begins a rising idea (Ex 2.27), which forges another link between finale and slow movement by extending both Exs 2.11 and 2.18. Midway through the ascent through the orchestra's compass, the full orchestra joins in in the eight note mode, violins taking Ex 2.27 still higher amidst versions of the earlier pervading rhythm (Ex 2.17 bar 4), the descending motif from Ex 2.17 bar 1, Ex 2.25, the augmented chord, and chords of B major and F# minor. These all resolve at V into chord Ib in the home key (the final chord of Ex 2.28, which summarises the passage from S to V), which is affirmed by a triumphal version of Ex 2.18.

Now that the four note mode's place in the proceedings has been demonstrated, some new chords may be used: for example, to the notes B flat and E flat may be added not just G, but A flat or F. Indeed the dominant seventh is now available, but Alwyn has so much creativity and unfinished business left that he makes us wait a long time for it, leaving the present climax poised on a unison dominant (W+5).

What follows is something characteristic of Alwyn's work, a type of long, slow, mostly quiet preparation for an ending, drawing together and resolving a number of themes, threads and arguments occurring earlier in or running through the symphony. A note of caution may be sounded here, for if one is not aware how many things are happening, such a passage may well sound tedious and unnecessarily long. The performer has an important contribution to make by not wallowing and ensuring that the music keeps moving. We are fortunate in the existence of a very fine recording of this symphony, conducted by its composer, illustrating how this may be achieved and succeeding especially well in the "drawing together" section of the first movement.

It would be very tedious to list all the significant events in this calm music. One should note when the timpani begin insistently and peacefully tapping out the progression from dominant to tonic, culminating at Z in the long awaited perfect cadence in E flat major. As if to confirm that the music has reached the harmonic goal towards which it has always been striving, the cadence is reiterated following a reminder of the four note mode in the form of Ex 2.27: after this, the music becomes even more peaceful. Since Y something else has also been taking place: the composer has taken the second half of a new (but beginning with G-F#-E flat) motif for cor anglais and expanded it into a horn call (Ex 2.29), showing that even at this stage it is not too late for new developments.

We have almost certainly forgotten the melody (Ex 2.6) from the B major climax in the first movement, and probably did not notice a bassoon motif (Ex 2.30) at G in this movement's development. Just as we think everything has been resolved into a peaceful conclusion, they appear as theme and countertheme, generating the loudest noise we have heard for several minutes and showing that Alwyn is too fine a craftsman to leave such loose ends untied. This leaves the music poised, quietly again, on repetitions of D#-B-G-F# (the augmented chord and its false resolution expressed as single notes), ready for the final masterstrokes. F# minor is finally resolved in quiet chords (top line E flat-F#-G) accompanying a descending "scale" beginning with G-F#-E flat and ending with B-B flat-G, leaving a solo violin alternating very high B and B flat in a manner reminiscent of the alternation of G and F# that led to the first movement's final outburst.

The four note mode has been forgotten again: suddenly it breaks out, returning us to the fast tempo and the rhythm of Ex 2.20. Having been assimilated earlier, it is no longer menacing, and after a crescendo happily resolves onto a unison E flat. A triumphant blast of E flat-F#-G concludes the symphony.