Orchestral transcriptions

An accompanist is often faced with special problems when called upon to play transcriptions of orchestral music. Generally, one feels more freedom to make alterations to these scores, because it is rare to utilise a piano accompaniment when mounting public performances of such music.

Reasons why reductions of orchestral scores may be excluded from concert programmes include the thought that listeners nowadays have easy access to live and recorded performances of concerti in the forms intended by their composers, and that however refined a pianist's skills, he cannot recreate the richness of texture of an orchestra (Adler, p. 174). It seems reasonable to assume that exceptions may be made in cases where a composer has transcribed his own work specifically for performance with piano (rather than as a means of improving access to his work before the age of recordings), or where performers have decided by intelligent assessment and good taste that a transcription is capable of being performed convincingly, taking into account the differences in texture and being prepared to adjust accordingly matters such as tempi.

One expects to play transcriptions of works for solo and orchestra in competitions and examinations, and orchestral reductions come into their own to enable such performances. One should not neglect the role played by these arrangements in giving opportunities to soloists and choirs to give performances that they would otherwise be unable to present.

Occasionally one encounters an arrangement for solo and piano made by the work's own composer, for example Saint-SaŽns' Violoncello Concerto in A minor or the Flute Concertino by Gordon Jacob. In these cases, there seems to be an obligation to attempt to play everything that appears on the page, on the grounds that it is an integral part of the composer's conception. This attitude may be tempered by considerations such as whether the arrangement was intended for public performance or for private use, as well as those of technical difficulty, occasion and advance warning.

There are sound, practical reasons for simplifying orchestral transcriptions. One often encounters in concerto accompaniments and vocal scores piano parts that seem at best to have been written with scant regard for piano technique, full of features such as wide, rapid leaps and fast runs in double notes; or at worst to be direct transcriptions onto two staves of the orchestral parts. If it is annotated with the original instrumentation, the latter type is useful as a study score, but makes a rehearsal pianist's job very hard work: however, it could prove a very helpful source from which to make an accompaniment, since a highly skilled player can vary his tone in a manner appropriate to the orchestral colours the soloist or choir will eventually hear, and all concerned may therefore benefit from the accompanist's having this information.

Possibly the best method to use when making transcriptions for piano of orchestral accompaniments is for a pianist, having listened to the music, to work at the keyboard, trying out different versions before writing them down. Theoretically, this is the approach most likely to result in a playable piano part that represents well the original score. When dealing with such orchestral music, it is often advisable to employ the art of compromise at the transcribing stage as well as the playing.

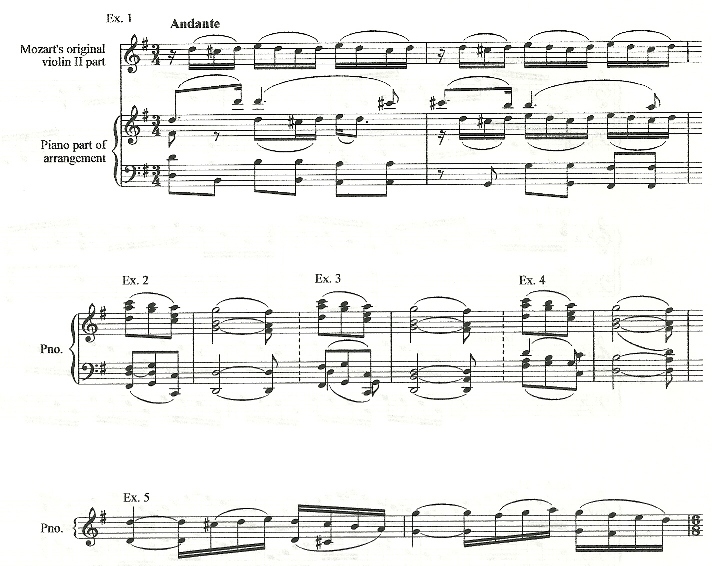

One difficulty in determining the best way of transcribing a passage arises from differences in technique and hand size between transcriber and user. Something many pianists find easy may well be impossible for many others: further amendments that a user may have to make range from merely spreading chords to more complex simplifications. The author of this essay can easily stretch a tenth between notes of the same colour: players with smaller hands may well be obliged to change or spread the first chord in the left hand of his transcription of Sussex Carol (Ex. 7), or further reduce his rendering (Ex. 1) of the turning accompaniment figure in bars 43-44 of the second movement of Mozart's Violin Concerto in D major, K211.

Transcribing orchestral accompaniments for piano gives rise to a number of problems that can be solved in a variety of ways. Being a pianist is an asset in the choice of solutions that are sensible, rather than likely to force the majority of players to find alternative, technically easier answers whilst not having access to the original score. Ideally, one aims to produce something that sounds as near as possible to the original: therefore, whether one is transcriber or player, it is advisable to listen to an orchestral performance before starting work. In order to make the score playable by two hands on one keyboard, it is often necessary to use devices such as omitting doublings (wholly or partly), transposing parts into a different octave, or omitting selected notes. The last two apply especially when an accompanying figuration played by more than one instrument is written in such a way that to transcribe it exactly would result in awkward, unpianistic repetitions of notes.

When making these simplifications, it is tempting to adopt the easiest versions to play of passages and cadences, which will often amount to an adequate representation or realisation. Occasionally, some of the essential effect of the music may be lost by this approach: one may often find in works by Mozart that the sound of a passage is characteristic of its composer by reason of unusual spacing of chords or octave doublings of parts, in which case one should make alterations only if the result of not doing so would be unplayable. A case in point occurs in bars 7-8 of the second movement of Mozart's Violin Concerto in D major: it is tempting to imitate the expanse of the texture of this cadence and its approach by preserving the double bass line, perhaps as in Ex. 2, but to do so whilst retaining the G in the final chord of bar 7 and the doublings of inner parts in bar 8 would result in muddy, low chords (Ex. 3). For these reasons, the author prefers Ex. 4. Another example occurs in bars 27-28, where a legato melody is played in octaves over quaver chords: in view of the difficulty of playing legato octaves on the piano with one hand, Ex. 5 is suggested as an appropriate compromise.

The slow movement of Mozart's Bassoon Concerto (Boosey & Hawkes, 1947) contains a good example of a piano part that contains as much of the composer's original orchestral writing as it is theoretically possible to play. To render fluently and musically such passages as the first half of bar 9, the third quarters of bars 12 and 37, and bars 39 to 42 requires an extremely high degree of facility and independence of fingers, and it is easy to find notes (for example, the lower B flat in the first chord of bar 39, and the G in the second chord of bar 41) which may be omitted without detriment to texture or harmony. Conversely, the texture in bars 43 to 44 is so characteristic of Mozart that it is advisable to play as printed.

The definition of the term unplayable is not absolute. Whereas a composer's work defaults to writing for musicians with fully professional techniques who may welcome challenges to stretch their abilities even further, a transcriber's work is hardly ever heard on the public concert platform. The range of accompanists for whom he writes encompasses all, from virtuosic pianists with plenty of time to prepare for rehearsals, competitive festivals or soloists' examinations to students sight reading at college master-classes. This is one reason why it is not clear whether some concessions should be made by the transcriber, or whether he should assume he is writing for someone with great technical facility, and that anyone playing his work will have the skill to make all compromises himself.

Opera

A repetiteur working in an opera house is likely to be very rarely satisfied with printed scores, finding them largely impractical sources for what the singers require from him, and preferring to virtually create his own score, adding and removing details as appropriate. As Jeremy Silver (repetiteur at English National Opera and conductor of Camberwell Pocket Opera, in an interview with Erik Retallick, postgraduate student of Canterbury Christ Church College, on 18th November 1997) puts it:

"... there will very rarely be double basses or piccolos in the repetiteur's version. I play with a different logic in places. It adds more depth of sound which is what the orchestra gives you. ... there are counter-melodies missed out, so you put them in. ... there are a whole lot of extra semiquavers, so you get rid of them. You end up changing the whole thing around."

A good example of a reduction of an orchestral score that appears to demand of a pianist an unreasonable degree of agility and accuracy in frequent leaps, not to mention many rapid notes, occurs in the vocal score of Mozart's opera Don Giovanni published by Boosey and Company in 1946. In fairness to the originators, this does not purport to be a piano part: it is simply presented on two staves with no suggestion as to instrumentation. From the repetiteur's point of view, this is unhelpful: it would be far more practical to be presented with something playable, that would not force him to devote a lot of concentration to deciding what to omit, especially since he is probably not familiar with the original scoring and consequently may not always make the best decisions.

Examples of how a pianist might deal with a few of the problems found in Act 1, Scene 1 of this score include omitting the lower notes of the chords on the upper stave in bar 18, since the harmony note is found in those on the lower stave; playing the triplets in bars 20 and 21 in the upwards direction or as unbroken chords (easier than playing downwards and still giving the singers the harmony and bass line); playing only the upper notes of the octaves in bars 22 and 31, giving secure harmony and rhythm whilst avoiding unwieldy jumps; and omitting inner parts when repeating chords in bars 57 to 60 (Ex. 6).

If he had occasion to consult the orchestral score, the accompanist may also consider recreating by means of articulation the antiphonal dialogue between strings and woodwind in bars 57 to 60; playing the original violin parts instead of what is printed in bars 20 and 21; and playing tremolos in bars 71 and 72. In this last example, Mozart's original consists of bowed tremolos: it is a moot point whether or not the given broken chords and runs are easier to play or more effective.

Choral Music

When a choral concert is given with piano accompaniment, the pianist is likely to be obliged to play keyboard parts intended for the organ, necessitating considerable preparation in the form of deciding which notes in the inner parts to omit or transpose so as to preserve both the bass line and the harmony. This is another area in which knowledge of the original (if that is an orchestral score) may help, for example in No. 12 of Handel's Messiah (edited by Watkins Shaw, Novello Handel edition, 1958): in the first bar, the tenor line is not to be found in Handel's score, an addition which seems strange given that the extra notes duplicate notes appearing in the melody or bass line. The six bars of introduction to this number could be performed convincingly by simply omitting the tenor line: in the first five bars, only on the second beat of bar 2 would a harmony note be lost.

Shaw designed his keyboard part in Messiah to be used in this way when played on the piano: it is more usual to be presented with scores written specifically for organ, including long pedal notes in the bass, which the piano cannot sustain even if it is physically possible to reach them with the fifth finger of the left hand. Repetition of the bass note is the least alteration that may be required: one may reasonably expect also to change the octave of several bass notes and to re-space chords. A suggestion for the left hand of the opening of a piano arrangement of the organ part for Sussex Carol (arr Willcocks, Carols for Choirs 1, Oxford University Press, 1961) is given as Ex. 7.

Some good examples of amendments that a choral accompanist may make arise in Mendelssohn's Elijah, published by Novello & Co in 1903. The opening of No. 29 may be improved by straightforward means of either omitting lower octaves wherever necessary to enable realisation of the lower stave with the left hand, or playing the upper line of the lower stave with the right hand.

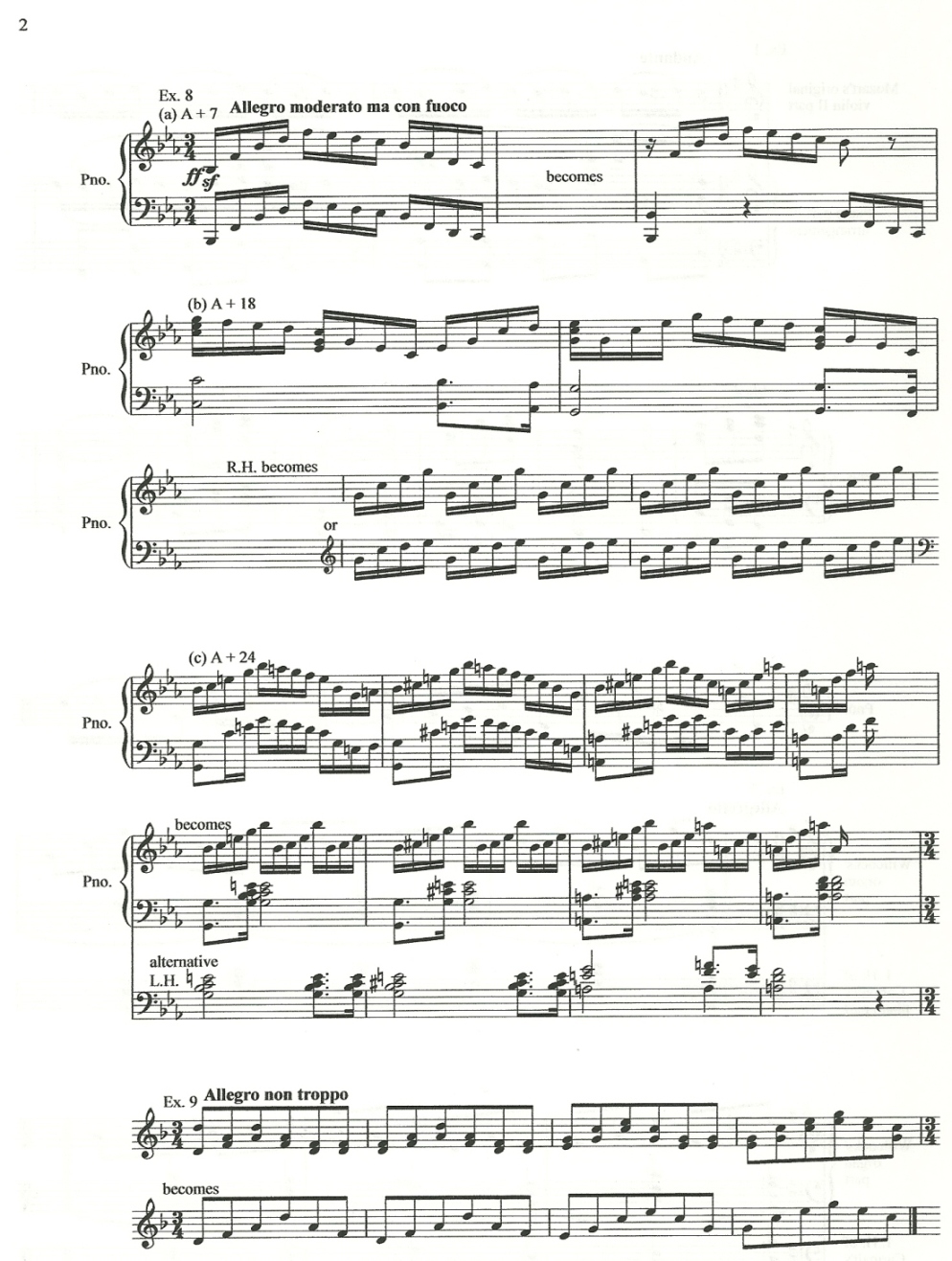

A more complicated problem is presented in No. 20: the effective representation of rushing waters is best left to be accomplished by the orchestra, and this number contains plenty of examples of figurations that may harmlessly be altered (Ex. 8), or played by one hand rather than both. Possible solutions revealed by the miniature score include: at A+7 referring to the chordal woodwind writing in one hand and the rushing string motifs in the other; or at A+24 deriving a left hand part from the wind and bass.

It is unlikely that in a performance, anyone would attempt more than the upper line of the extremely difficult repeated chords in the right hand in the second section, Hear us, Baal, of No. 11: in a rehearsal one would certainly not do so, and in the four bars before B one would use a simpler, more pianistic figuration than that which is printed (Ex. 9). At B+8 one is presented with rapid two note chords for both hands, at which point this becomes an example of a reproduction on two staves of the orchestral parts, rather than a piano part. A sensible solution would be to continue playing the upper line of the right hand part, while the left hand plays chords (to give the harmony), or doubles the choral part at the octave below. Again, the orchestral score reveals a better possible arrangement, taking the top line of the violins' parts in the right hand, and the lower octave of the woodwind's in the left.