Methods

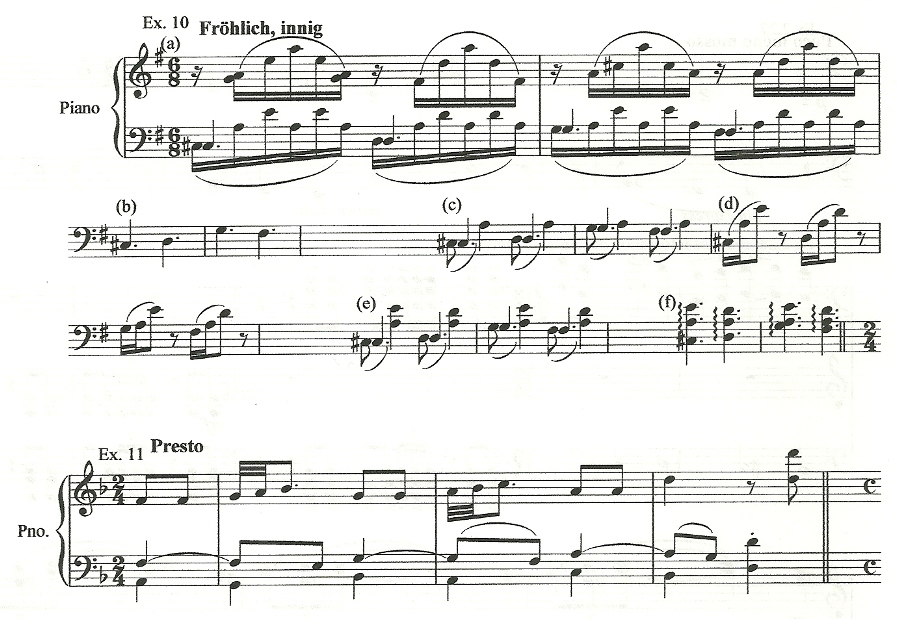

More examples of devices that may be used to facilitate playing a difficult score include omitting notes played or sung by other parts, and altering the shape or reducing the number of notes per beat of figurations, always identifying the harmony and ensuring it is complete. When sight reading No. 7 of Schumann's Frauenliebe und Leben (Dover, 1981), one may well resort to playing only the bass line of the left hand part (Ex. 10b), which would secure the rhythm while the right hand provided the harmony. It would not matter if one did not observe the change in shape of the right hand figuration in bar 6, but one would try to inject harmonically important notes such as the D#'s in bars 14 to 16.

An excellent sight reader, or someone who had minimal time to prepare for playing this song in a class, might attempt a version from Ex. 10c-f in the left hand. With insufficient time to master the piano part before an examination, one might improve one's chances of clear rendition of the bass line and harmony in such a passage as bar 6 by omitting the fourth and sixth semiquavers in the left hand, ensuring that one plays the correct notes in the right hand even if the fourth and fifth become reversed. One would certainly not wish to accept any of these devices in a public performance or in an exam, especially if the pianist were the candidate: in a singing exam, the priority is to provide the candidate with an accompaniment that appears to be correct and does not contain distracting errors.

If one were performing No. 3 of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro (Schirmer, 1951), one may wish to make one or two omissions in the central presto. At this tempo, it is not possible to execute a trill on a semiquaver, so one would probably employ an acciaccatura at most; in each of the first three of the last seven bars, one might leave out the second quaver in the left hand. It is very unlikely that a listener would notice this, although arguably one should not give a public performance of this piece without including these notes since they resolve suspended sevenths, which are significant elements of the harmony (Ex. 11). A credible alternative solution could be to forego the suspensions by playing a succession of sixths with the left hand.

A good example of a very difficult piano part, in which differing degrees of compromise may be acceptable according to the occasion, may be found in the Grand Duo Concertant for clarinet (or violin) and piano, Opus 48, by Weber (Peters, no date). This is specifically a duo, that is the composer intended it to be a virtuoso showpiece for both instruments, and one could be excused for asserting that on those grounds no omissions or amendments are acceptable. Whilst one should certainly aim for this situation if giving a professional concert performance of the work, that attitude will not help a clarinet student, wanting to offer this piece in his exam, to find a partner.

In the first movement, the piano part may be made even more difficult if the soloist fails to understand that Weber's qualification con fuoco of his allegro is not the equivalent of a vertical line through his common time signature, and that there are four beats to the bar rather than two. This essay is not the place for an in depth discussion of such matters of interpretation. For the time being, two points should be observed: that expressions such as con fuoco are indications of mood, and are helpful in determining articulation more than speed; and that whilst the tempo may be derived from the instruction to take four beats to the bar, it may be advisable to think of two or even one beat per bar for the sake of phrasing. A soloist (or soloist's teacher) may or may not be amenable to having such matters pointed out by an accompanist.

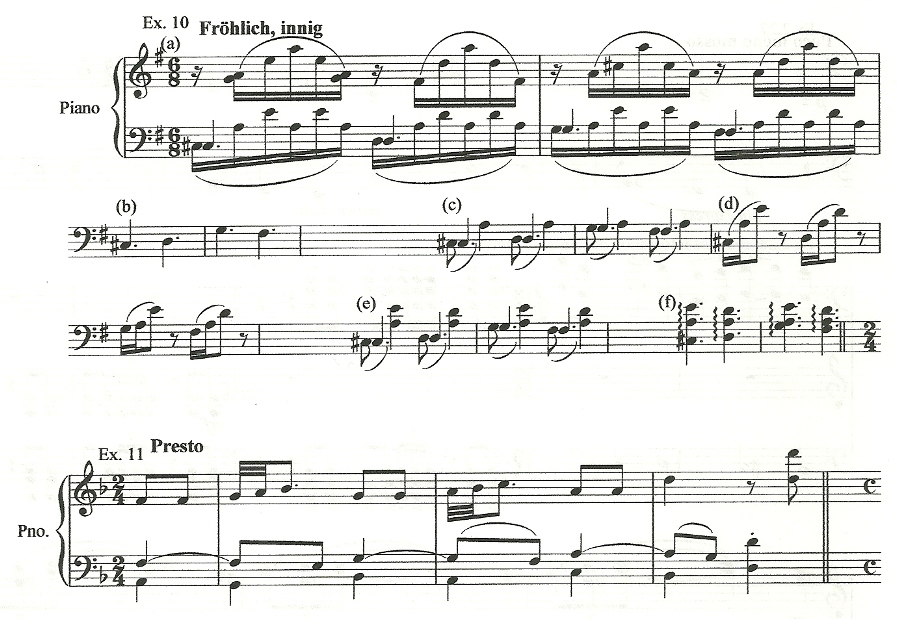

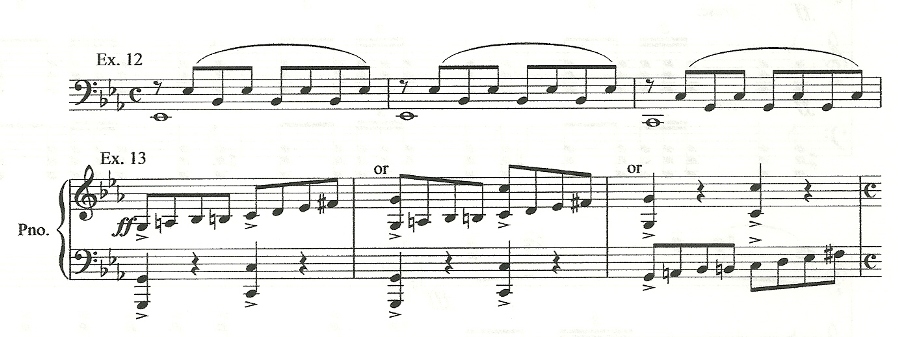

If conditions are such that one is obliged to play this movement without being able to prepare it ideally, the first thing that may be omitted is the last note in the left hand in bar 2: this should not be noticed, and ensures that the chord in bar 3 is safely reached. In the two bars before A, one may consider leaving out the grace notes, but only as a last resort, since to do so would significantly alter the character of the music by substituting a smooth line for one that is lively: it should therefore never be contemplated in front of an audience, and preferably not in front of an examiner. Simplifications that may be deemed acceptable in a clarinet exam include: amending the left hand figuration at A, so as to remove the jumps (Ex. 12); at B+5 playing what Weber wrote with one hand while the other plays octaves on the first and third beats of the bars (Ex. 13) (better than playing only the scales: to remove the octaves would alter the character of the music); and not being concerned three bars later if one finds it necessary to continue the figure with only one hand.

Further compromises that might be considered in this movement include: utilising chordal left hand accompaniments at D, the beginning of the development section, and G+6 (Exs. 14-16); at D+11 playing as chords only the most important notes in the left hand part (Ex. 17) (this alteration to the character of the music is another that is best avoided if possible in an exam as well as in a concert, especially since this passage is a piano solo); at E taking the bass F's an octave higher, whilst ensuring one plays at least the first and last notes of each group of four in the right hand; and omitting the left hand part of the chords on the second beats of the fifth, seventh and ninth bars of H, playing the descending arpeggio in the tenth in only one octave.

All these suggestions are for alterations that might be planned in advance to improve the likelihood of giving a musical account of the piece when conditions are not ideal, and that may lessen the frequency of instant compromises when mistakes are made during the performance.

Conclusion

It is hard to say what conclusion (if any) has been reached by considering the art of compromise, and its role in the work of the piano accompanist.

Most of the points raised are matters of technique or musical interpretation. In general, it is dangerous to give dogmatic answers to problems in these areas, because the former can depend on such issues as the size and shape of the individual player's hands and physique, whilst the latter varies according to taste, developments in performance practice and historical research, and is renowned for generating strong and contradictory opinions, all of which can be demonstrated to conform to composers' markings. Indeed, it is in the nature of true art that it is enriched by the wide range of conflicting individual responses it arouses.

The foregoing chapters serve to demonstrate that there is such a thing as compromise in musical performance, and that while it takes place behind the scenes, it may still be acknowledged as a vital element in a player's range of skills, and used not as an excuse for deficiencies, but as a positive means of improving the quality of performances.